Hiroshi Sugimoto, 167 Olympic Rain Forest , 2012 © Courtesy Gallery Koyanagi

Sugimoto exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo

30/04/2014

Could beauty be the world’s salvation?

The first things we see are the tyres—many tyres, mountains of tyres, and barricades of tyres.

© Autoportrait de Hiroshi Sugimoto

However, this has nothing to do with Sugimoto’s exhibition; it is the work of Thomas Hirschhorn, whose exhibition opens on the same day, at the same venue—the Palais de Tokyo—, and as part of the 2014 program ‘L’Etat du ciel’ (‘The State of the Sky’).

Well, visitors will say to themselves, Sugimoto—the ‘Living National Treasure of Japan’, the master of incessantly renewed photographic seascapes, with their impeccable and consistent geometry—will be something else. With Sugimoto, we’ll be immersed in typically Japanese—minimalist, pure, and precise—aesthetics. Not at all: you’ll leave behind Hirschhorn’s dirty tyres only to be faced with Sugimoto’s rusty sheets of iron.

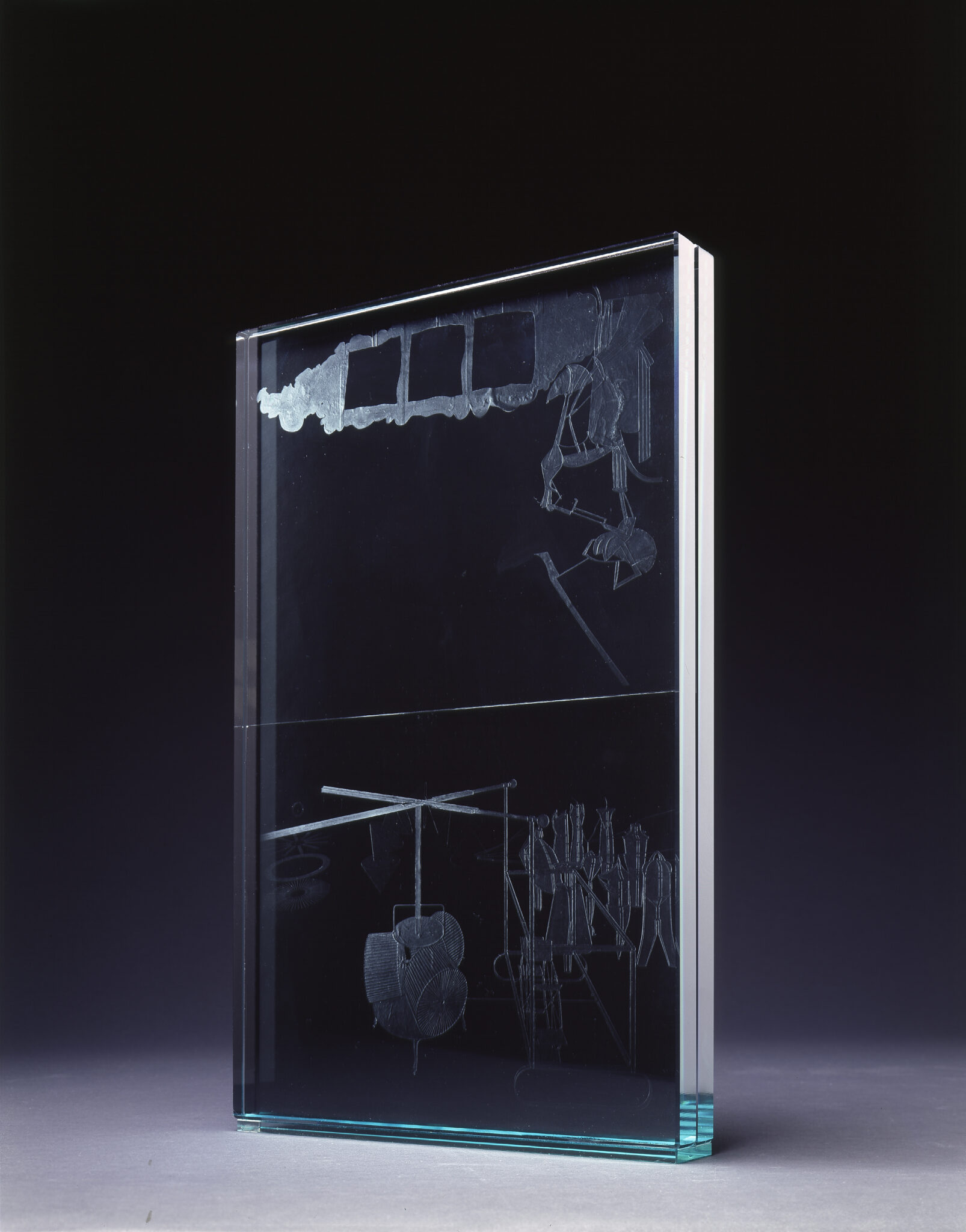

In any case, dear visitors, you will not be visiting an exhibition of either artist in the usual sense. You are not invited to ‘visit’ their work; there is nothing here, a priori, that is intended to arouse your sense of wonder (a priori, we’ll see later); not with Hirschhorn, who is presenting an exhibition that provokes thought and encourages exchange (will it lead to a ‘revolution’, or just disruption—or not even that? Perhaps the intended effect is subversion; if there’s poetry it’s already a good thing, isn’t it?). The same thing applies to Sugimoto, who proclaims that ‘Le Monde est mort’ (‘The World is Dead’). He proclaims this and repeats it endlessly in a whole series of catastrophist scenarios—from the extinction of the mammals to the end of procreation due to sexuality confined exclusively to inflatable dolls. An obsession? Not at all—it’s more of a surrealistic joke and ridicule. It makes one think of Breton’s Petit Dictionnaire de l’Humour Noir. And Sugimoto sees himself as the natural successor of Duchamp, whose influence is evident throughout this installation. All the same, the ridicule is highly cultivated—after all, the venue is the Palais de Tokyo, not the Théâtre des Variétés.

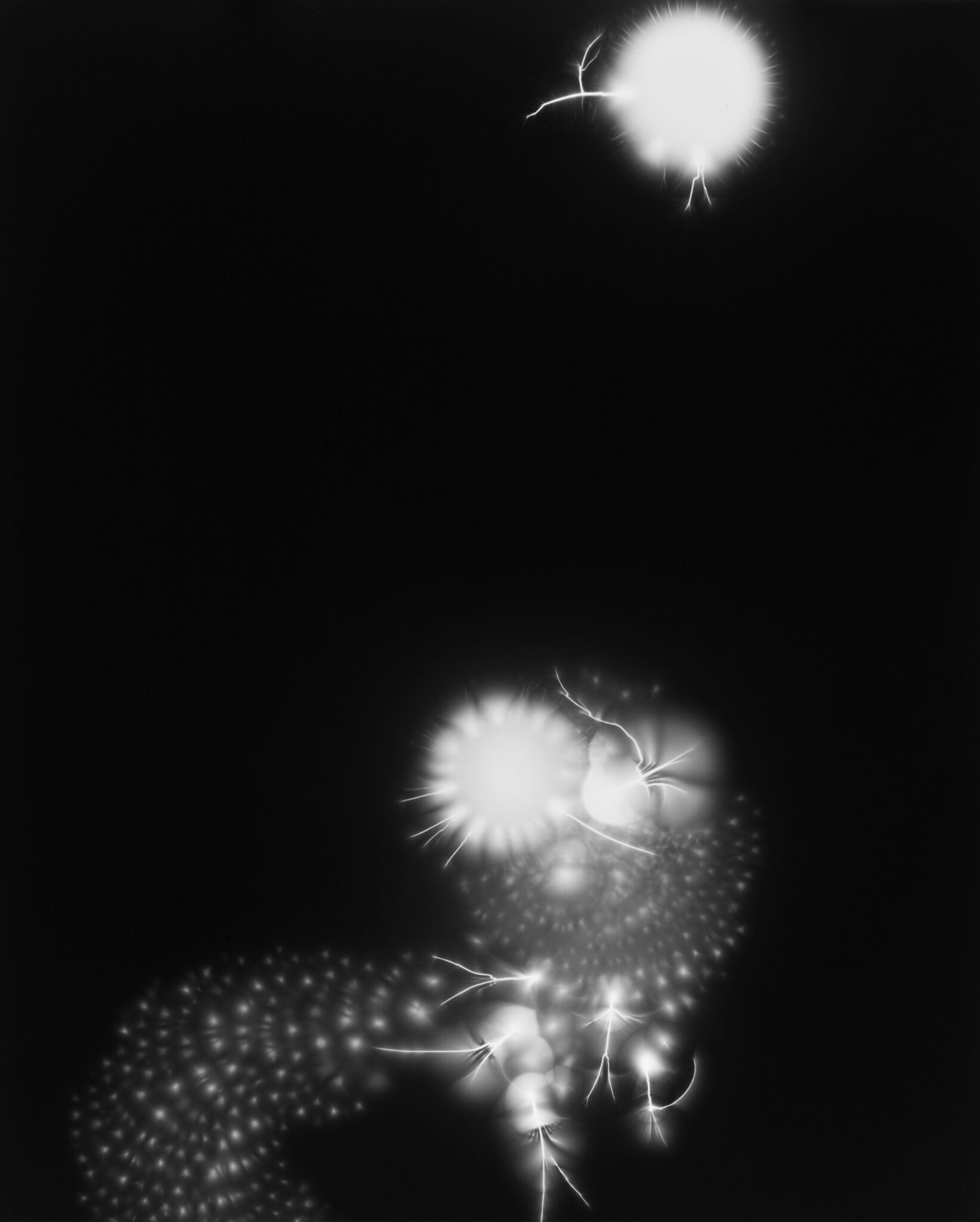

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Lightning Fields 138, 2009 © Courtesy Gallery Koyanagi

At the top of the solid stone staircase is a thirteenth-century Japanese god—a god of anger—, a precious item from the private collection of Sugimoto, who was an antiques dealer before ‘being an artist’.

The god is not happy with what man has done to his beautiful planet. He stands next to a Duchamp-style bottle rack; Warhol-style cans, which the artist tells us will soon be worth less than the real ones full of good soup in the supermarket; a meteorite that has shattered the glass roof, the steel beams, the concrete floor—the Palais de Tokyo has really gone to town—, and the Duchamp urinal on the next floor down; and a very ‘cute’ inflatable doll, which is also Duchampian. Throughout the exhibition, manuscripts written by Sugimoto tell us how humanity will eventually disappear. Yves Paccalet would have said ‘good riddance!’ Apart from the god of anger, Japan is as predominant as Duchamp: calligraphy, Hiroshima, and, above all, a traditional tombstone, which brings together the five fundamental elements of Shintō-Buddhism: earth, water, fire, wind, and the sky (cosmos). On Mount Kōya, the thousand-year-old remains of two hundred thousand samurai warriors have been marked by similar stones amongst cedars that are several hundred years old.

Sugimoto takes the theme of the tombstone further, by placing a smaller, crystallized stone in front one of his photographic masterpieces of the sea. ‘Has it been found? Eternity, that is; it’s the sea…’

Moreover, in the transition between the dead or half-dead world and eternity, between the tombstone and the glittering crystal, Sugimoto creates beauty. Did he intend to? Or is this just the visitor’s perception? In any case, after the chaos of the rusty iron sheets at the beginning of the exhibition’s itinerary, we find ourselves in a fine, impeccable straight corridor, lined with new designer iron sheeting painted in light grey, at the end of which is a ‘Sugimotian’ photograph of the sea.

The stories about the end of the world are not so funny, but a serious and exhilarating question does arise by the time one leaves the exhibition: could beauty be our salvation? In Japan, France, and throughout the developed and the developing world, we could create beauty: more beautiful cities, coastlines, suburbs, and metros, instead of larger ones. In short, a quest for perfection, as Louis Roederer would say…

‘L’Etat du Ciel’ – Part 2 – ‘Aujourd’hui le monde est mort’ (Today the World is Dead’), Hiroshi Sugimoto, Palais de Tokyo, Paris – 25 April to 7 September 2014

With the support of the Louis Roederer Foundation, a Major Patron of Culture and the Arts.