Ana Elisa Sotelo

Amérique du Sud

La nature et l’interaction humaine avec le monde naturel constituent les thèmes centraux de l’œuvre d’Ana Elisa Sotelo. À la suite d’une fracture de la colonne vertébrale qui bouleverse sa vie en 2016, l’artiste découvre le pouvoir de guérison de la médecine traditionnelle amazonienne, ne cessant ensuite de documenter les liens entre santé naturelle et spirituelle. La série proposée, Portraits of the Multiverse, présente une interaction entre photographie et broderie. Ana Elisa Sotelo a en effet collaboré avec l’artisan d’art péruvienne Sadith Silvano pour créer un dialogue entre les mondes du visible et de l’invisible, soulignant le lien profond entre l’Amazonie, ses habitants et leur art ancestral. Une façon de rappeler l’urgence de préserver cet écosystème irremplaçable et ses cultures. Multi récompensée, Anna Elisa Sotelo a notamment remporté l’International Women in Photo Award en 2021 pour son projet Las Truchas, qui célèbre les nageuses de Lima au Pérou, symbole de la résilience de la communauté pendant la pandémie.

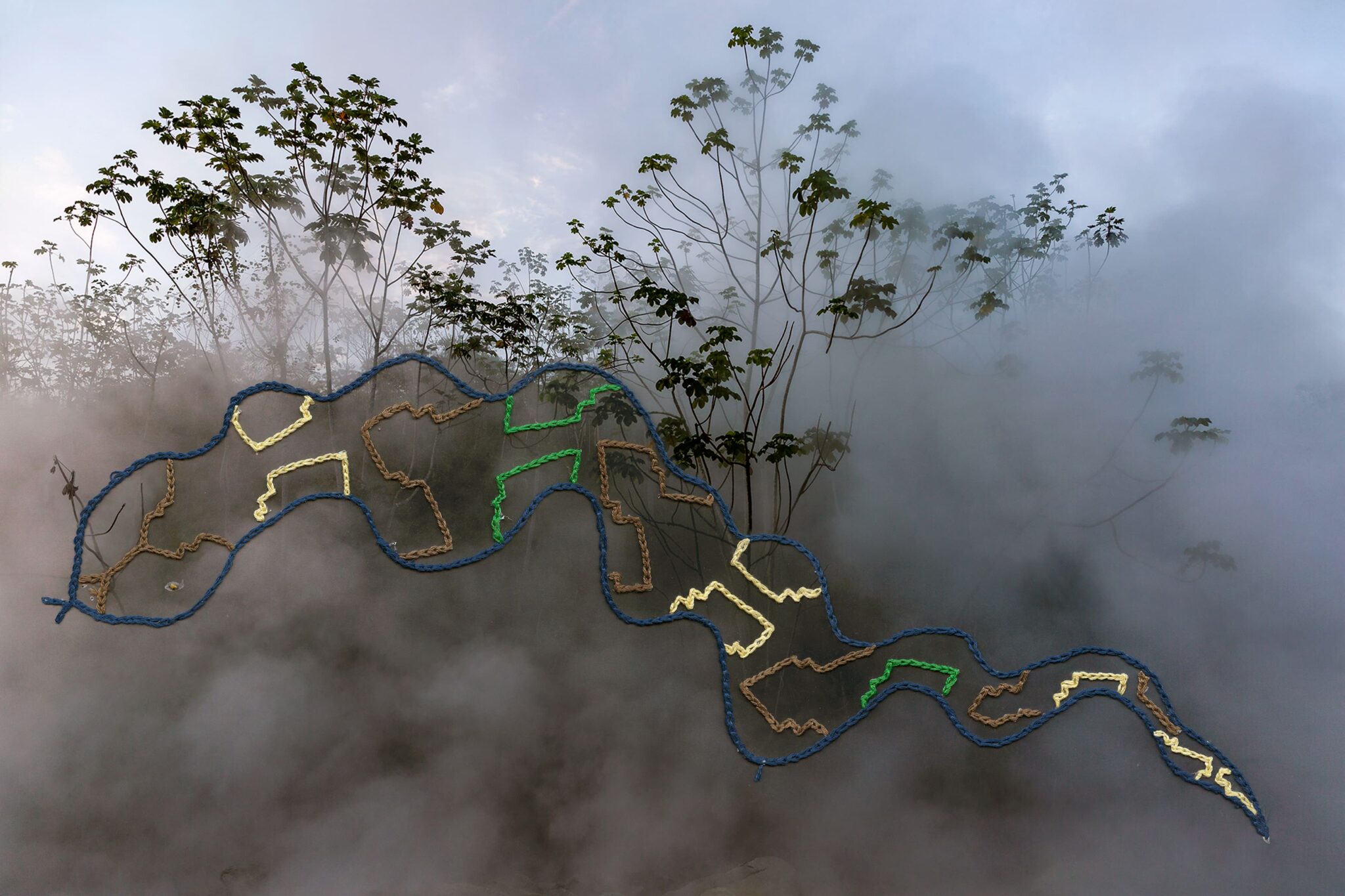

© Ana Elisa Sotelo & Sadith Silvano, The Shanay-Timpishka River (part 1), Portraits of the Multiverse

La pratique d’Ana Elisa Sotelo ne donne pas seulement un aperçu des langages contemporains de la photographie et de son potentiel en produisant des liens entre l’image capturée les techniques et l’histoire ancestrales de la broderie et de la peinture Kené. Il traite également des questions de durabilité en remettant en cause la fracture coloniale qui sépare l’humain du non-humain et produit un système mondial extractif. J’ai proposé sa candidature pour le prix parce que je crois que cette façon d’aborder la pratique artistique est essentielle pour changer la façon dont nous percevons et expérimentons le monde.

À propos de la série

« Portraits of the Multiverse est une recherche visuelle en cours entre Sadith Silvano, maître de l’art Shipibo Konibo « Kené », et moi-même. L’art Kené illustre la composition vibratoire sous-jacente de l’univers. Cette collaboration découle d’un besoin de rendre visible l’invisible et se compose de photographies brodées et de vidéos d’accompagnement.

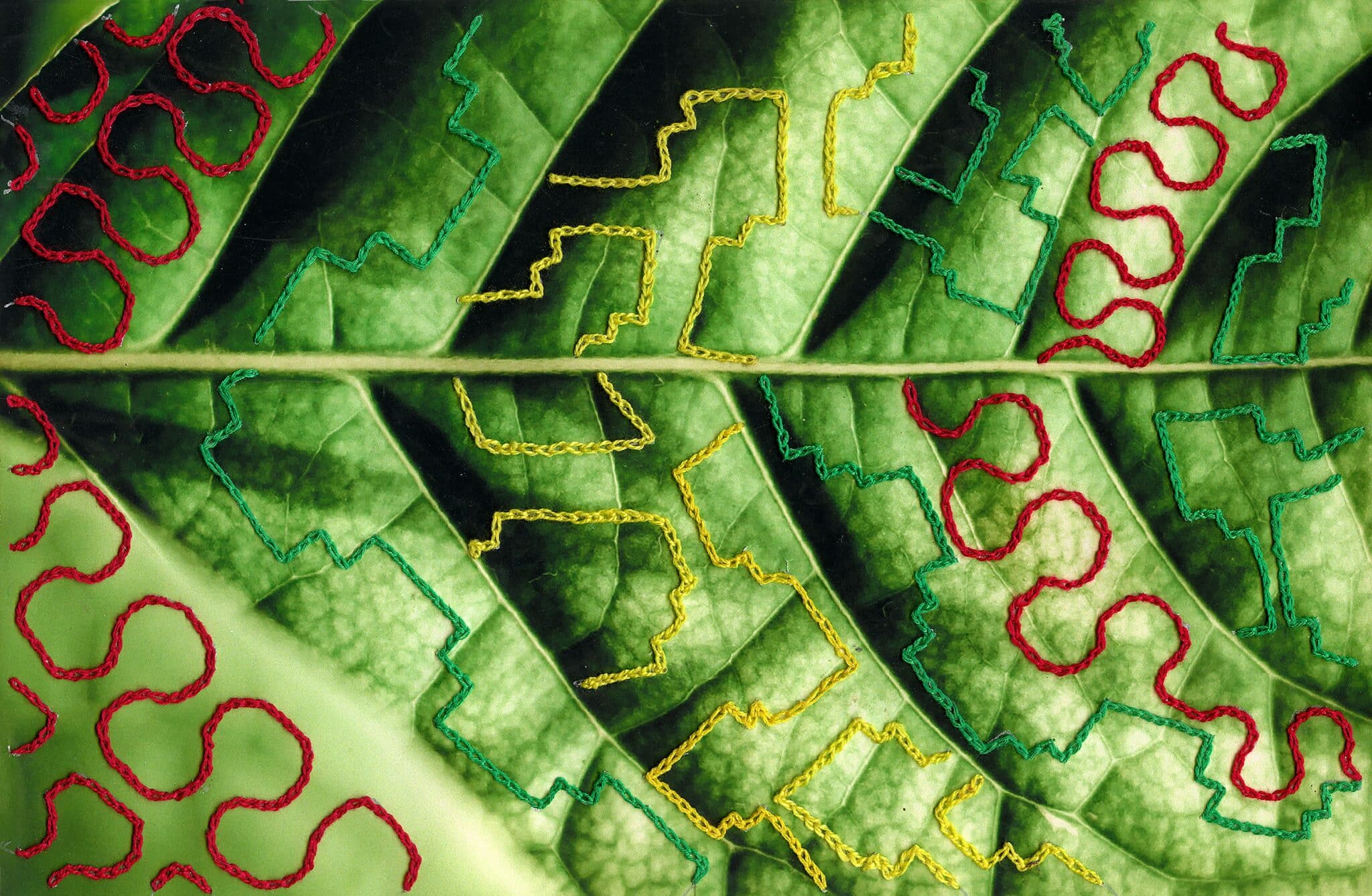

Dans ce travail, je présente des éléments de l’Amazonie, tandis que Sadith révèle l’énergie immatérielle qui règne dans la jungle à travers la broderie. Les images sont prises sur les rives des rivières Shanay-Timpishka et Nanay. Actuellement, cette région, comme une grande partie de l’Amazonie, subit une déforestation massive à un rythme alarmant. La forêt primaire est rasée pour faire place à des terres agricoles, ce qui entraîne non seulement la disparition de la flore et de la faune, mais aussi un changement culturel et une modification de la relation entre les habitants de la forêt et de la terre. Dans un paysage où territoire et culture sont inextricablement liés, la disparition des forêts entraîne la disparition des esprits et de l’âme de la jungle. Le peuple Shipibo de l’Amazonie représente et rend visible ce monde depuis des milliers d’années par le biais de la forme d’art « Kené ». Les femmes Shipibo sont formées dès leur plus jeune âge à « voir » et à comprendre le « Kené » Elles accèdent à ce monde par le chant et l’absorption de plantes sacrées qui révèlent des visions de cette énergie. L’artiste Shipibo Sadith Silvano rend ce monde visible en brodant « Kené » sur mes photographies. Chaque pièce représente une rencontre entre deux univers : le matériel et l’immatériel. En passant du monde invisible au monde visible et en revenant à l’invisible, cette série développe un dialogue sur le multivers amazonien. Il s’agit d’une rencontre visuelle entre deux langages qui capturent la lumière par des moyens différents : la photographie pour l’un, la broderie pour l’autre.

Le résultat est cette série de photographies brodées qui illustre la riche diversité de l’Amazonie, englobant non seulement la biodiversité, mais aussi les traditions culturellement riches de ses habitants et de son art. Chaque pièce cherche à documenter l’importance de ce paysage en voie de disparition, en soulignant les aspects culturels et environnementaux de l’Amazonie. » – Ana Elisa Sotelo

Statement

« Portraits of the Multiverse est une recherche visuelle en cours entre Sadith Silvano, maître de l’art Shipibo Konibo « Kené », et moi-même. L’art Kené illustre la composition vibratoire sous-jacente de l’univers. Cette collaboration découle d’un besoin de rendre visible l’invisible et se compose de photographies brodées et de vidéos d’accompagnement. Dans ce travail, je présente des éléments de l’Amazonie, tandis que Sadith révèle l’énergie immatérielle qui règne dans la jungle à travers la broderie. Les images sont prises sur les rives des rivières Shanay-Timpishka et Nanay. Actuellement, cette région, comme une grande partie de l’Amazonie, subit une déforestation massive à un rythme alarmant. La forêt primaire est rasée pour faire place à des terres agricoles, ce qui entraîne non seulement la disparition de la flore et de la faune, mais aussi un changement culturel et une modification de la relation entre les habitants de la forêt et de la terre. Dans un paysage où territoire et culture sont inextricablement liés, la disparition des forêts entraîne la disparition des esprits et de l’âme de la jungle. Le peuple Shipibo de l’Amazonie représente et rend visible ce monde depuis des milliers d’années par le biais de la forme d’art « Kené ». Les femmes Shipibo sont formées dès leur plus jeune âge à « voir » et à comprendre le « Kené » Elles accèdent à ce monde par le chant et l’absorption de plantes sacrées qui révèlent des visions de cette énergie. L’artiste Shipibo Sadith Silvano rend ce monde visible en brodant « Kené » sur mes photographies. Chaque pièce représente une rencontre entre deux univers : le matériel et l’immatériel. En passant du monde invisible au monde visible et en revenant à l’invisible, cette série développe un dialogue sur le multivers amazonien. Il s’agit d’une rencontre visuelle entre deux langages qui capturent la lumière par des moyens différents : la photographie pour l’un, la broderie pour l’autre. Le résultat est cette série de photographies brodées qui illustre la riche diversité de l’Amazonie, englobant non seulement la biodiversité, mais aussi les traditions culturellement riches de ses habitants et de son art. Chaque pièce cherche à documenter l’importance de ce paysage en voie de disparition, en soulignant les aspects culturels et environnementaux de l’Amazonie. » – Ana Elisa Sotelo

Regard d’auteur

Pictures also sing: photo-embroidery in the multiverse

Version originale en anglais

Photographs also sing. Their voice is an embroidered thread on their bodies made of paper. Such words come to mind when I see the artistic work of Ana Elisa Sotelo and Sadith Silvano. The photo-embroidery series Portraits of the Multiverse is born from the confluence of two different graphic epistemes that met at the Boiling River in the Peruvian Amazon, in the Ucayali basin, land of the Shipibo-Konibo people. Ana Elisa went there searching for healing with ancestral Amazonian medicines made from the bark of the Came Renaco trees growing on its banks. When she was undergoing her plant therapy, she made pictures of the river sanctuary and its steam. Back in Lima, she took her photos to Sadith in Cantagallo, the urban Shipibo-Konibo community in the polluted and hectic heart of the Capital.

“Tell me what you see in these photos I took of my relationship with the river and its plants,” she requested and explained she had drunk Came Renaco and Ayahuasca during her healing journey. “I felt many things, but don’t know what happened. I could only take pictures of what I was seeing, as a visitor.” Sadith looked at the photos with the eyes of someone who was raised in a family of visionaries. Since she was a child, she grew up surrounded by Kené and learned to find it, even if it were not visible, guided by the visionary skills she inherited from her elders. When Ana Elisa suggested she should intervene with her ancestral art in her photos, Sadith patiently hollowed out the embroidery path, opening pores on the paper before passing the thread through.

Kené is a visual language of geometric patterns composed of strokes of varying thickness and color generating games of light and contrasts between background and figure. Its purpose is not so much to explicitly reproduce the figures of the beings around, as to reproduce what makes these beings capable of action. Kené catches the eye, forcing it to complete the figures that insinuate themselves between the lines without ever remaining fixed.

Unlike photography, it does not capture the light of surrounding beings to reveal their images, but rather reveals and cleans up their usually invisible energy circuits, illuminating them through traces of color. This bright full energy, or as expressed in Shipibo-Konibo, Koshi, is a key feature of powerful cosmic beings with shiny skins, providing them with a hypnotic and fierce beauty. Such is the case of the spots on anacondas and big cats, both animals standing at the top of the forest predation chain, or the star-pierced path of the firmament and the veins of plant leaves that grant health, thought and skills.

The work of crisscrossing photography and embroidery was done in polyphony, sometimes with convergent melodies, other times in independent routes. “Water is a very strong healing space to me,” claimed Ana Elisa, who swims regularly and water is a constant motif in her work. In the pictures Ana Elisa took, Sadith saw, dancing on the river steam, the designs of Ronin, the cosmic “mother” of water and Ayahuasca. According to Ana Elisa, when she drank Ayahuasca as part of her therapy, the very plant “called out for other plants” to come and gather in her healing. Sadith had also drunk Ayahuasca. “In my case, I got to talk with Mother Ayahuasca who is La Abuelita (The Endearing Grand Mother). She told me there are many kinds of Kené designs, the ancestral and the contemporary. Each woman works in her own way following her inspiration”. That’s why Sadith embroidered on the picture of an Ayahuasca leaf with red, yellow and green threads, some more recent curved designs as well some older designs with right angles, placing their lines “face to face”. Such a “duality”, she explained, “represents us, humans”.

In each new picture, each artist told her own life story. While Ana Elisa saw that she had taken a photo of her extended hand requesting help from the river and plants, Sadith saw that her own hand was portrayed as a vehicle of knowledge from her mother and sister. “Our hand is magical; you receive, you also give. Thanks to my hand´s energy I am now the woman I am. I can do what I set my mind to, thanks to my Kené.”

The flow of Kené Sadith embroidered on the picture moves onto Ana Elisa´s hand. The designs enter the photograph through its frame with a thick line tinted with blue, which moves in steps with broken angles and is superimposed on a thinner golden line, which moves in curves. Both threads arrange themselves on the palm of the hand forming a head-shaped pattern. Then, the golden embroidery frays over the wrist. It gives the impression of floating above its veins or, depending on how you look at it, of surging from its blood as a spring of Kené dancing up into the sky.

Such a game of perspectives is what Sadith calls “face to face”: It applies everywhere, curved and broken, thick and the thin, what receives and what gives, what comes and what goes. Everything has its pair. “Duality” everywhere engenders the perceptive dynamism of Shipibo-Konibo art. The ghostly aesthetic of the river captured by the camera lens contrasts with the neat strokes of the Kené the camera did not see, calling into question what is real. Portraying the multiverse may mean trying to encompass all the versions of worlds that make it up, but this is never possible. Each version has its other side, which is never just its reverse image; and when one side is seen more clearly, the other one shallows, and transforms, in an incessant play between background and figure. Kené invites the viewer to flow along with multiplicity knowing that the visible and the invisible coexist in motion and may never be encapsulated in a fixed thoroughly comprising image.

In the last picture of the series, the embroidered cloak embellishing the bather/mermaid’s tail “represents me,” both artists said. Ana Elisa made a picture of herself swimming in her favorite “healing space” and Sadith saw in it her own image, “my own empowerment, my livelihood”. Like a mermaid´s cloak, she explains, “Kené is my faithful companion. It never leaves me.” She now lives and works in Lima, but even in the midst of urban frenzies, her Kené unlocks the healing energies hidden in Ana Elisa´s picture. Their photo-embroidery casts spells. It wraps us with the Amazon´s breathing waves. I wish I were a mermaid too. Maybe that’s why such a seemingly dissonant phrase comes to mind: photographs also sing. Their bodies breathe in and out with the needle of Kené. This photo-embroidery series is a masterfully achieved work of creativity and thought, each artist experimenting with their techniques in pas de deux, “face to face”.

Biographie

« Je suis artiste et photographe, je viens de Lima, au Pérou. J’ai grandi entre le Pérou, la Bolivie, le Mexique, les États-Unis, l’Argentine et le Chili. Aussi, la curiosité envers le monde et ses cultures m’a été inculquée dès mon plus jeune âge.

La nature et notre interaction avec le monde naturel sont des thèmes que j’explore et que j’étudie constamment dans mon travail visuel. Je travaille actuellement sur les liens entre l’écoféminisme et l’image. Lorsque je fais de l’art, j’invite souvent les participants à interagir, à s’interroger et à partager leur relation avec l’environnement par le biais d’une action collective et d’une performance.

Mon intérêt vis-à-vis du pouvoir de guérison de la nature a commencé en 2016, lorsque j’ai souffert d’une fracture de la colonne vertébrale et que l’océan de Lima m’a guérie. Cette année-là, alors que j’étais en mission en Amazonie pour la National Geographic Society (NGS), j’ai rencontré le maestro Juan Flores, un guérisseur traditionnel Ashaninka et Shipibo, qui a soigné ma blessure par la médecine traditionnelle et des chants. Ce fut mon premier contact avec le monde spirituel de l’Amazonie. Cela a grandement influencé ma pratique artistique me conduisant à explorer la relation entre le monde naturel et la santé humaine.

En 2022 j’ai assuré une partie de la direction photographique du documentaire Entyo et j’ai rencontré l’artiste Shipibo Sadith Silvano. C’est à cette époque que j’ai subi une nouvelle blessure et que je suis retournée en Amazonie pour guérir, me reconnectant avec le monde spirituel de la jungle. J’ai partagé mon expérience avec Sadith et nous avons créé ensemble Portraits of the Multiverse. »

Licence en psychologie à l’Université George Washington (Washington D.C.)

Maîtrise en documentation à l’Université américaine (Washington D.C.)

Lauréate de l’International Women in Photo Award (2021) avec le projet Las Truchas devenu The Wild Swimmers

Lauréate du Picture of the Year Latam Award (2023) avec The Wild Swimmers enrichi au Chili grâce au Women Photograph Grant (2021). Le projet montre des femmes qui s’engagent auprès de la nature d’une manière non extractive, tout en développant des modes d’interaction réciproques, proposant ainsi une alternative à la manière dont nous habitons le monde.

Exposition à Lima, Paris, Tokyo, Genève et Alemería

Publié dans le Washington Post, le National Geographic, Vogue, El Comercio, El Mercurio, Where the Leaves Fall, Fare Magazine, entre autres